Regional vernacular architecture has always been a personal interest, but specifically the forms rooted in Texas history. There is so much unique vernacular architecture in the various areas of the United States, but Texas itself has many unique regions. Perhaps the most interesting and applicable in current residential design are Central Texas and the Hill County. The architecture of these areas derives from the earliest settlement and particularly in primitive shelter and agrarian structures. The early structures were simple forms made from locally available materials and free from the clutter of unnecessary detail. They convey design and construction approaches brought from the place of origin of the builders. All respond directly to their surrounding environments and natural sites.

Considering some basic definitions, “regional” addresses a geographic area distinguished by similar features. The term “vernacular” refers to a language, specifically native to a region, a non-standard language of a place, region, or country. Texas is a large and varied state containing many different regions, each with a distinctive character, defining features, and other characteristics that distinguish each area from another. Architecture consists of form plus structure, the root “archi-“ meaning primitive, original, or primary. It is the art or practice of designing and building structures, especially habitable ones. Combined you get Texas Regional Vernacular Architecture.

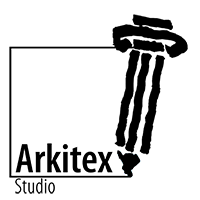

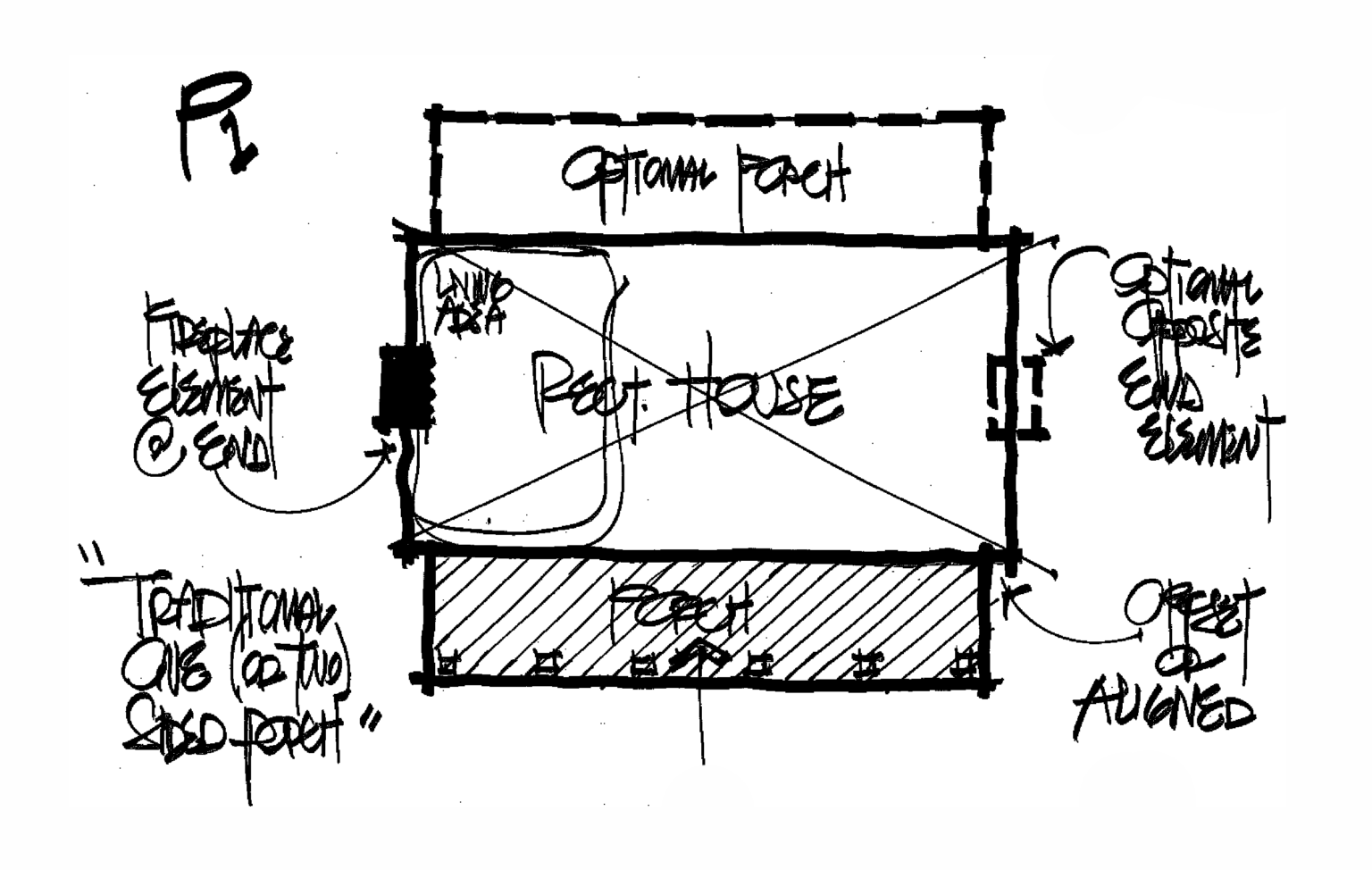

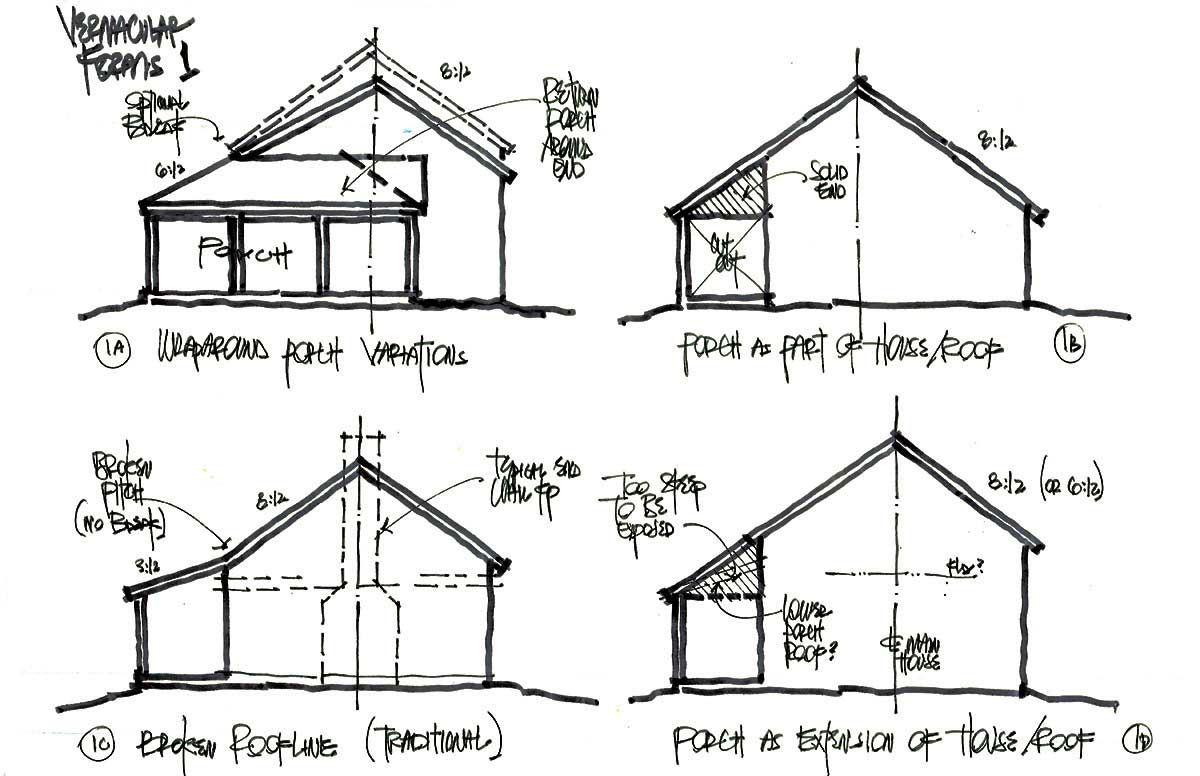

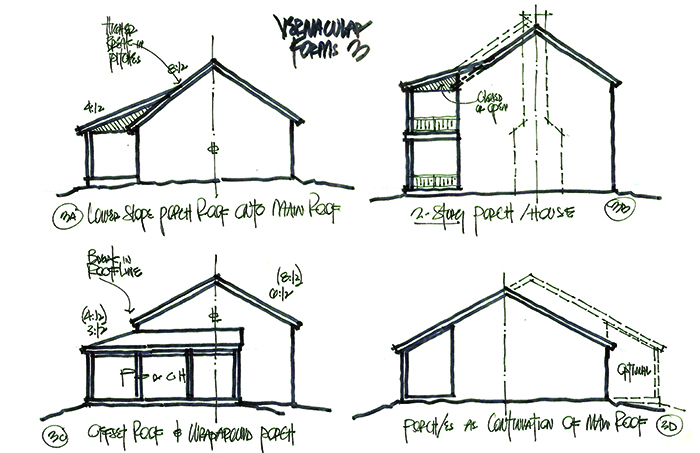

Considering form, there were initially very natural forms (responsive to their settings), geometrical forms (for practical reasons), and the principle of addition and removal from the core structure. The principle of contrast appeared in the use of various forms and materials in combination for aesthetic reasons as well as the availability of new materials over time. Simplicity out of practical necessity gave way to decoration of various types. Vernacular forms included porches as extensions or removals from the main structure, wrap-around porches, continuous versus broken rooflines, two-story main structures, offset rooflines, two-story porches, and many other variations. Roof pitches and material applications affected the overall form as well. Structures might have a single porch attached to the main structural mass or multiple porches, such as front and back, front and end wrapping around a corner, or even three- or four-sided porches. While these choices affected the visual character, they were motivated by functional issues such as shading, protection of walls and possessions, and other functional considerations. They could be extensions of the main roof or articulated by offsets, changes in roof slope, and supporting posts or columns.

Another major visual feature was the fireplace which provided heat and was used for cooking. Usually on an outside wall (often the North wall), they added a new element of form to the composition. Fireplaces were often of a contrasting material (such as stone combined with a wood structure), and they were sometimes found on each end of the structure.

Distinguishing features also included native materials, natural to the area and readily available. These included logs, wood siding and shingles, stone, bricks, mud, stucco, and eventually metal cladding, especially roofing. Uses depended on availability, applications, and combinations of different materials, always with simplicity of form and ease of construction. Structures were intended for habitation, holding livestock, storage, specific agrarian functions, and eventually commerce and communal activities. The root forms were Texas primitive farms and ranches of early settlements. The designs were motivated by the need for basic protection from the elements and intruders. Concerns were natural ventilation, protection from the elements, providing natural light, and shading from the relentless Texas sun.

What often began as a one-room structure evolved over time by adding porches, room additions, or combining multiple structures, often with “dog run” porches between them. With porches visual changes included a variety of roof forms (such as the shed roof), posts and columns, partial walls, and various degrees of openness. Other additions were often a cooking kitchen area, separated from the interior due to heat generation, dedicated sleeping rooms, and of course the separate outhouse. Adding onto the original structure over time, the most primitive structures would be recycled for other functions such as barns, storage, and other agricultural uses. The most simple of structures initially provided to meet basic needs began to evolve into farm/ranch compounds of structures, and over time these became settlements, villages, towns, and ultimately cities.

An example of a modern interpretation of these historic forms would be my own house which is based on the iconic “Sunday Houses” unique to the Fredricksburg area. Originally these in-town homes allowed residents of remote farms and ranches to venture to town on weekends to shop, socialize, and worship. Having begun as one-room houses, they had been expanded over time and were eventually left to their children while they retired to town. The classic form includes the steep-roofed central mass (usually with an upper sleeping loft accessed by an outside stair), a wide front porch, and a rear shed-roofed wing (for the kitchen and sleeping rooms).

Today, architects look back on these historical roots with a backward glance at the old styles that influence modern designs. Many of today’s Texas regional vernacular houses are inspired by simple barns and one-room dwellings, many of which remain as aged agrarian buildings. The designs still authentically respond to the natural environment, to their specific sites, to honest materials from the areas, and convey timeless design principles still applicable today. They look like something rooted in the past but with more modern design sentiments and heightened attention to sustainability and energy-efficiency.

Written by Charlie Burris, AIA