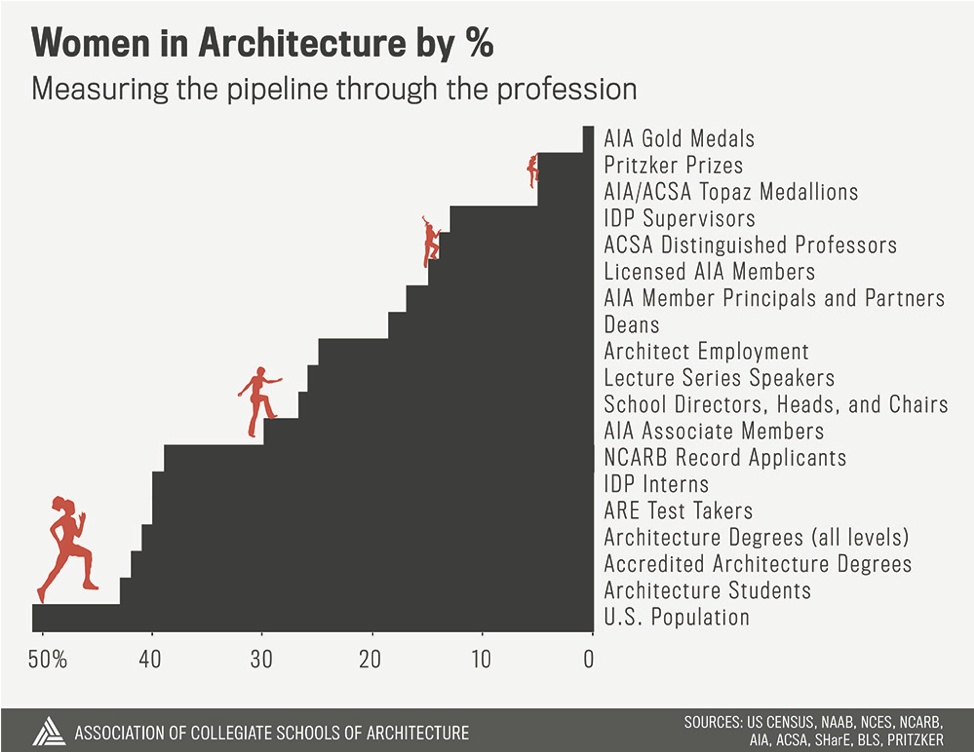

Hopefully today, when one thinks about the role of women in any profession, one does not give a second thought about gender and a person’s ability to perform in their job. Haven’t we been at this long enough to be past that issue? After all, the ‘Women’s Movement’ as it is officially documented in the history books, was over 100 years ago. In the architecture profession, women are still a fraction of the firm leaders by comparison to men. However, this is not the case in schools. Looking at the current demographics of architectural education, we see that the number of women in architecture schools equals the number of men. (At Texas A&M’s College of Architecture, the number of women is actually 54.7%.) In high school, women are performing at equal or higher levels in comparison to their male counterparts, thus being accepted into architecture schools at high rates. While in college, these women are also performing at high levels in all aspects of their education and training.

When I was in architecture school in the 1980s, the number of women was not at the level it is today. Women were definitely the minority. So, the change in our culture and educational system has obviously changed to make this path more accessible. So why then, when we look at the demographics of the practicing profession, does the number of women drop so dramatically?

I would argue that this is still a larger cultural issue. The expectation is still for women to be caretakers of both children and aging parents as their primary role. During my childhood, my mother was one of the very few working moms among my classmates. She was ahead of her time as a medical researcher and professor at a medical school, yet she was the one that addressed her children’s sick days, forgotten lunches, and after-school activities. Somehow she managed to do it all, albeit she had no fellow women to share the hardships she encountered by living in these 2 worlds. (I never knew as a child the sacrifices she made; and now can only infer from my own experiences how difficult hers must have been in the 1960s and 70s.)

Now, that is not to say that today women still often choose to be the one to call when a child becomes sick while at school. As a mother myself, having to make a choice between a sick child and a project meeting, I would definitely choose my daughter (though my spouse has always been readily available to share these responsibilities.) But why does there have to be a choice for a mom between her child and her job?

My experience as a female in architecture has varied from welcoming to hostile over the course of 30+ years in the profession. I remember receiving ‘cat calls’ on construction sites, being told to ‘not get my panties in a wad’ when in a heated discussion with a contractor, and receiving backhanded compliments about my performance (‘for a woman she is really competent.’) But I have also had a number of very supportive male mentors and peers throughout these years whose support far outweighs those negative experiences. Who hasn’t, be they male or female, received ugly comments from another? And hopefully we all choose to focus on the more positive moments.

It is not those negative moments that are the issue, in my opinion, but a culture that still structures job expectations on a 1950’s model. Work can be done outside of the typical 8am to 5pm hours, allowing a mom or dad to go see their child in a school performance. Holding a job position for a person on family leave to care for a dying parent not only allows that architect to return to her/his much-needed job but also avoids brain-drain for the firm. Creating an atmosphere that allows employees flexible schedules and a culture where team members cover for and support one another, regardless of their gender or status in the profession, is one way to address the need to balance life’s various priorities and challenging moments.

I believe in time that the architecture profession, as well as other male-dominated fields, will ultimately achieve a culture that allows for all voices to be heard and to participate, helping our profession better serve all clients and projects. After all, shouldn’t our profession reflect those whom we serve?

Resources and further reading:

The American Institute of Architects:

https://www.aia.org/articles/13086-diversity-not-a-women-only-problem

The Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture:

Written by Eva M. Read-Warden, AIA