How do you replace an existing building within a constrained and historic campus? From a strict preservation standpoint, the answer is simple: don’t. Sometimes, though, that is not an option and the answer is much longer.

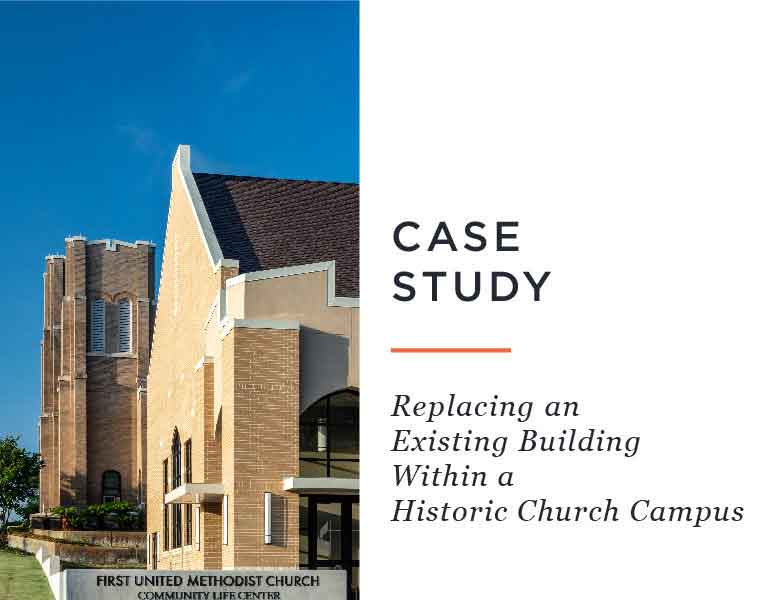

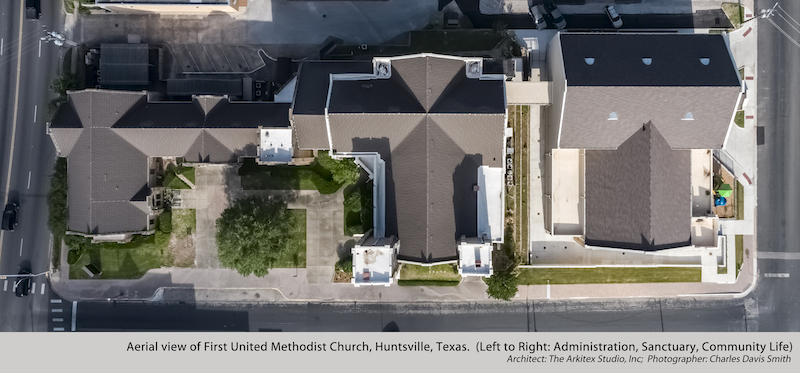

At First United Methodist Church (FUMC) – a church campus located off the courthouse square in Huntsville, Texas – changing needs had made replacement of the 1970s Social Hall with a new Community Life Center the only realistic choice. However, the Church valued their campus’s history and setting and wanted to treat both with sensitivity. Over the span of four years, The Arkitex Studio worked with FUMC to develop and achieve a plan for a facility which would help the church better serve the community at large as well as their own congregation, without creating conflicts with its context. Key elements of the process that allowed this project to succeed included programming for diverse current and future needs, designing the new facility to connect visually and physically within the context, and finding the right project delivery method to see it successfully constructed.

Programming

Religious buildings serve many people with many different, and sometimes conflicting, priorities and desires. During the programming phase, architects met with the Building Committee to learn about the church’s needs and aspirations. They also collected information on goals and motivations from the congregation through surveys of small group gatherings. This allowed all relevant parties to provide input and created a large data set. From this, the architects sifted out wants versus needs and maximized efficiencies at the project’s beginning, building a cohesive and balanced program of requirements.

Through this process, the church recognized the need to invest in their future by providing facilities to serve adults, youth, and children and that these groups need different things from their spaces. This led to the identification of spaces such as a multi-purpose sports court/contemporary worship and fellowship hall, a large kitchen, a variety of classroom sizes, and a dedicated youth gathering space. They also prioritized connection to the Huntsville community and the context of their historic church campus buildings – two factors which greatly impacted the overall design of the new building.

Design

Providing for the activities which will involve people from beyond the church forms the largest part of creating community connection. The events themselves and the types and sizes of spaces provided to serve them addressed this. However, newcomers generally hesitate to engage without an invitation (or at least awareness that there is something in which to engage). This led to a translation of the concept of connection into the overall form and layout of the structure.

Taking advantage of the urban setting, large windows into the multipurpose space, foyer, and coffee bar open these areas and their uses to passersby. The visibility of the children’s playground signals that families are welcome and provided for, while also easing oversight of and security for children using it. Placement of the main entrance at the corner of two public streets rather than off a private parking lot or through the main church indicates that the building is open to non-members. None of these things solidify the church and community’s connection on their own, but they all stand in support of FUMC’s efforts as a concrete (well, brick, mortar, and steel) example of what they intend to achieve.

In aesthetic terms, FUMC also wanted the new building to better connect to their existing buildings and downtown setting of the church campus. The 1970s social hall was a box-like structure, set back from the property lines and clearly an object distinct from the rest of the Gothic Revival-style campus of steep gables and masonry arches.

Being beside the town square, most nearby buildings are zero-lot-line structures. Since the campus is landlocked and they needed more floor area in the new facility, it made sense to extend the new structure out to the building limit lines, creating a better relationship with the sanctuary and administration buildings, as well as placing the entrance closer to the public sidewalk. Additionally, the building materials and form followed the original sanctuary’s precedent of tan brick and steep gables – although with simplified Gothic Revival-inspired detailing to avoid competition or confusion with the historic structure itself.

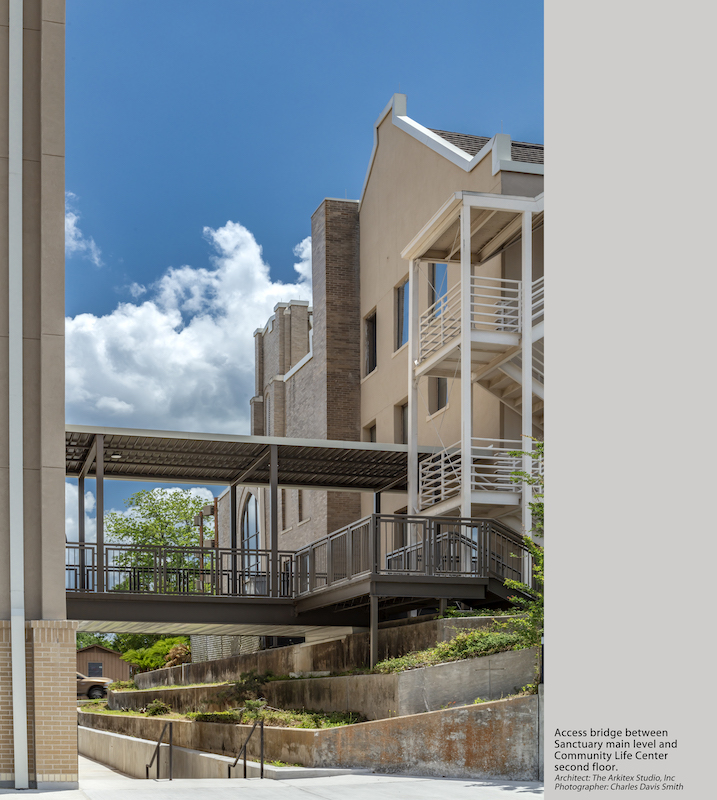

The final element of connectivity involved physical connection; getting people into, out of, and between the buildings. Though flat by comparison to some parts of the world, Huntsville’s topography is steep by the standards of much of Texas. The relevant portion of the site drops approximately 10 feet over 120 feet. This led to a system of retaining walls, drains, and strategically placed ramps and stairs to allow the passage of people and water as appropriate while conforming to the Texas Accessibility Standards (and, concurrently, the ADA guidelines).

To complicate matters, the new building needed a physical connection to the existing sanctuary at an upper level as well. This had existed in the previous social hall, but, being constructed before the enactment of ADA when landing sizes and floor slopes were less regulated, the existing bridge no longer met the definition of an accessible path and was difficult to navigate for someone with mobility impairment.

Since the existing building’s location and floor heights were, obviously, existing, the project could not rely on altering them. Area requirements and a constrained site also limited the placement of the new building. This meant that a first-floor elevation, necessarily accessible from the street level, and a second-floor elevation, set by the sanctuary building’s first-floor, limited the new building’s floor-, and therefore ceiling-, heights. At only 20 feet away from the existing structure, construction had room for less than an inch of error.

Project Delivery

With the need for this level of accuracy, as well as the situation of working in an urban setting on an active campus, the project needed a contractor not only skilled and knowledgeable in the construction field, but minutely familiar with this project in particular. Any worthwhile general contractor will know the building better than everyone else by the end of construction, but to have someone who would thoroughly understand it before construction began required a slightly less traditional approach.

Without going into a long explanation of the various project delivery methods used in the building industry (each with factors making it more or less suitable to a particular project), in most projects a contractor is not engaged until after the design is complete and the owner decides to start construction. Using a Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR) form of contract, however, involved the contractor during the design process. This is not necessary in many cases. Having the contractor on board early at FUMC, though, provided the architects with a resource to consult for advice in cost and constructability of design elements and meant the contractor knew the project, its complexities, and its critical elements long before construction began.

Over the project’s four years, it included many other factors and decisions. However, despite where this post started, exhaustive “how to” manuals in architecture are next to impossible. In broad terms, the premise of a solid team of owner, architect, engineers, and contractor, all willing to share their expertise and approach problems with as much care as creativity, improves the likelihood of success on complex projects. On this project, involving these team members early in the process also allowed them to provide more value, heading off or mitigating potential conflicts where multiple factors and constraints intersected.

While sacrificing an existing building is never easy, when a structure outlives its usability and has to be replaced, it is possible to do it well if you treat the setting with respect. The new Community Life Center’s design ties into its context and provides the space and flexibility to meet FUMC Huntsville’s needs for many years to come.

Post Written By: Pamela da Graça